It is good to be back with you after the hiatus in August-September. I enjoyed finishing up our six-part series in late July. For this month’s instalment of Sprachspielen and perhaps a few upcoming instalments, I’d like to get back to some basics with looking at a word that is really central to understanding what it is God has called us to do, how to do it, and with whom.

We’re going back to a term that is a major part of the tag line that usually follows the name of our organisation, Linguæ Christi, or our logo in print: “reaching the indigenous minority language groups of Europe.” Early in this series, we began to look at some of these terms. For example, in the Sprachspielen articles in June and July 2020, we looks at the term “groups,” specifically Linguistic Affinity Groups. In August 2020, we looked at what we mean by the word “indigenous.” In September and October 2020, “minority” was the subject for those months. And finally, in November 2020, we looked at the term “European.”

This month and perhaps for another two or three instalments to follow, we will be picking up the chase of considering the words used in our tag line by looking at concepts that include the word “language” or a derivative thereof. We will begin this exploration of the concept of language with the term “heart language.” As briefly as possible, therefore, I’ll be explaining some things that are foundational for us in our work, namely (1) what is a “heart” language, (2) why is it important in missions, and (3) why is it a central theme for Linguæ Christi, which we feel the need to repeat seemingly endlessly.

Let’s start with trying to describe a “heart language” as a concept and also in practical terms. I realise before I even begin that there will be some, who might say, “It’s obvious what a heart language is – it’s the language of a person’s heart. Why does it need explaining?” Though there might be some questions to ask syntactically and semantically about such a definition which relies almost completely on the primary words of the question itself, I feel that those who might question the need to define a term that seems self-explanatory to them probably also have some cross-cultural experience, which includes some exposure to other parts of the world and other languages. However, the reason that I feel the need to spend at least a few lines looking at the definition of a “heart language” is because of an encounter that I had a few years ago, while in the United States. I was speaking about our missionary work in a Church context, and as is my custom I opened the floor for questions. To be honest, most of the questions were not new to me. However, one person asked, “Could you explain what a ‘heart’ language is?” I was a little taken aback, because the answer to this question seemed painfully obvious to me. But as I took a moment to reflect on his question, before attempting a response, it occurred to me that I had spent most of my life in cross-cultural and multi-lingual settings as well as in missionary circles, and this term was so natural to me, I couldn’t really remember a time, when it was not familiar nor know any friends or colleagues for whom it was unfamiliar. I then tried to look at the situation from the perspective of the young man asking the question.

In my new friend’s query, I realised some things both about him and my audience more broadly. I realised that (1) he was probably monolingual; (2) he lived in a predominantly monolingual context or he spoke the dominant, majority or “trade” language in a bilingual or multilingual context; and (3) he was representative of the vast majority of the people from the USA, who pray and support us. For you see, the term “heart language” is really only familiar to those who live and function in multi-lingual settings or who are working cross-culturally and consequently multi-lingually, such as in missionary work, where the missionary comes from one cultural and linguistic background and goes to serve in a context that has a different language and culture.

The term “heart language” is significant in either bilingual or multilingual settings. The term is generally used to make a distinction between the language used by the local people in their linguistic areas and a “trade” language, which is generally a more commonly known language, often a world language and even more frequently a European world language. More often than not, the “trade” language is a language that has been forced upon local inhabitants, who have their own “heart” language(s), by dominant and colonising nations, whether from near (as in our context with minority languages in Europe) or from far away (as in European colonialism in other continents of the world).

The “heart” language, therefore, is that language used by a distinct group of people both (1) as a cultural, national, historical and even religious marker and source of identity in the more general or ethnic sense, i.e., for an entire ethnolinguistic people group, AND (2) the medium of identification and communication for the deepest, most intimate, and bonding areas of human interaction between members of the same ethnolinguistic people group as well as for accessing information at the maximum level of significance and comprehension possible. In missiological terms, the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL) would describe a “heart language” as “the most effective language for communicating deeply as well as for learning new concepts.” SIL would further consider the “heart language” as “the most important language for any given person, especially in multilingual contexts.” At a more visceral and intimate level, I would explain a “heart” language like this: when a bilingual/multilingual person reaches a point of suffering, despair, or anxiety that forces him to fall on his knees, look to the sky and cry out, the language of his cry is his “heart” language. It is the soul’s language of a human standing before “eternity and the universe” in secular terms, or before our Creator, the Lord God Almighty, as we Christians believe and profess.

Hopefully, this brief look at what we mean when we speak of a “heart” language has been helpful. But the next questions are, “Why should we care?” “What does this have to do with missions?” Most expatriate missionaries in the world as well as missions agencies would hold that it is essential to learn to communicate at a high level of competence in people’s heart languages and to use those languages for all points of interaction both interpersonally and in reference to the truth of the Gospel, even when those same people also have proficiency in a “trade” language, often a major world language, which is usually a carryover from the evil and excess of European colonialism. Take the African Continent for example. After centuries of European colonialism and control, a historical fact with significance in the present is that those colonial languages continue to be used for “official” purposes or as a means of communicating with people speaking numerous heart languages, a “lingua franca” of sorts. European-based people and even missionaries particularly from the Northern hemisphere continue to use the language of colonialisation, by describing these African nations as “Francophone”(French-speaking) or “Anglophone” (English-speaking) or “Lusophone” (Portuguese), etc. Because of the history of these nations, ability in one of these colonial languages, if not already existing, does need to be pursued, as there remains a practical need for the colonial, “trade” languages in many of these contexts. However, we would say that if a missionary really wanted to be effective in reaching a specific ethnolinguistic people group, he or she would also need to have as high, if not higher proficiency in the “heart” language of the people with whom the Gospel is to be shared. For example, let’s say that an English-speaking missionary family from Canada feels called to do missionary work in Ivory Coast. Because Ivory Coast is considered a “Francophone” country, they will probably learn French to a high level of proficiency (either in France or in Ivory Coast). But they will be trying to do evangelism, discipleship, and Church planting among people, whose heart language is Baoulé. Consequently, they will learn Baoulé (often through the medium of French) to a high level of proficiency in order to explain spiritual and abstract concepts to the people they are trying to reach with the Gospel through their “heart” language.

The scenario I’ve mentioned above would seem reasonable to most people looking at the situation from outside of it. More to the point, it would be familiar to most of us, as we’ve heard missionaries speak about such experiences. We would intuitively feel that sharing with people in their “heart” language would, therefore, be good missionary practice and a reasonable expectation. Most of us would feel that Nelson Mandela’s famous quotation on the matter says it best: “If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his own language, that goes to his heart.”

However, for those still unconvinced, I would offer some more ideas about the missionary necessity of communicating Gospel truth to people in their “heart” language, even if they speak other languages, and using that heart language in every stage of those conversations with people, from the simple personal interactions of day-to-day life, to Gospel conversations, evangelism, discipleship and new Churches all through the medium of the heart language. I feel that there are two broad categories of reasons for the use of “heart” language in missions.

The first of these categories, is what I would call the Biblical reasons. This is by no means an exhaustive or even comprehensive treatment of this subject. But hopefully it would be an introduction to the idea that the Bible has something to say about the use of language in the transmission of the Gospel and in the establishing Churches in every ethnolinguistic people group in the world, which are indigenous to those people and through their “heart” language. I like to call this the “Three M’s” of “heart” language mission (yes, there is alliteration).

Mandate

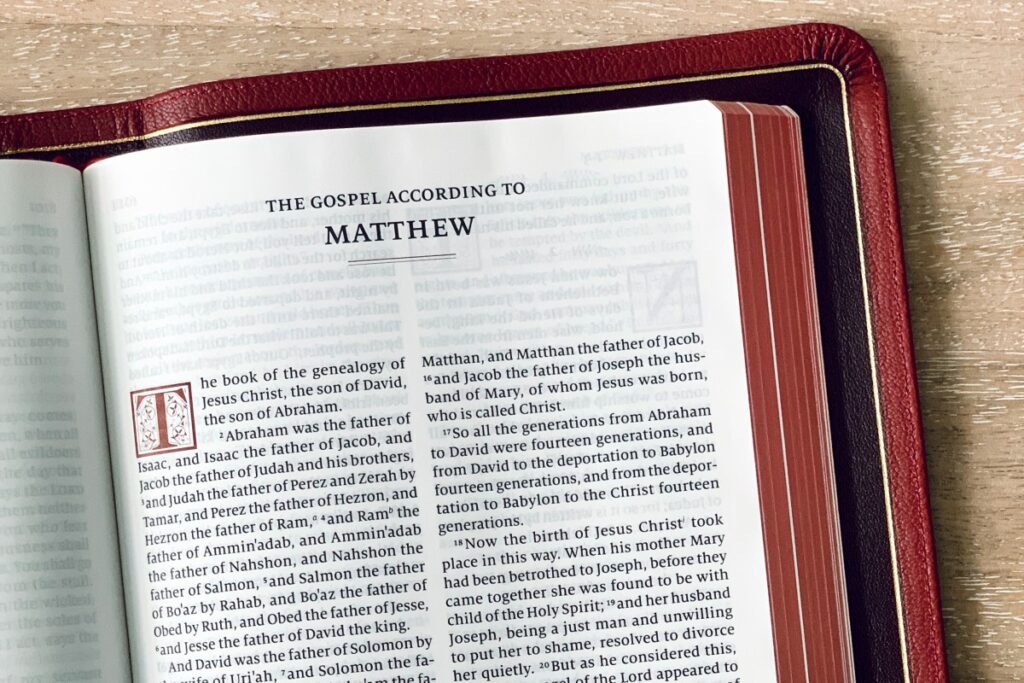

We would say that some attention to language is implicit in the Great Commission itself. In Matthew 28:19: “Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptising them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” – the term “all the nations” is “πάντα τὰ ἔθνη,” where “ἔθνος,” from which we derive the terms related to “ethnicity” in Engish, is actually closer in meaning to an ethnolinguistic people group, those who possess their own language and other cultural marks of identity and separateness. Consequently, the mandate is to all the language groups in the world.

Methodology

We actually see the principle of use of heart language in the Bible. I will simply mention two of these instances, both from the New Testament. First and probably the best known instance is on the Day of Pentecost, where people with various “heart” languages “hear them speaking in our own tongues the wonderful works of God.” (Acts 2:11). These were definitely distinct languages, as evidenced by the term διάλεκτος used in Acts 2:8: “And how is it that we hear, each in our own language in which we were born?” It seemed important to God in planting HIS Church at Pentecost that people, speaking numerous languages understand “the wonderful works of God” in their heart languages.

Second, we see multilingual Paul use “heart” language to make himself perfectly understood in Acts 21:37-22:29. Acts 22:2 is particularly telling: “And when they heard that he spoke to them in the Hebrew language, they kept all the more silent.”

Manifestation

We also have the end result of missions through the heart language, which is simply those whom Christ has redeemed from every language group, worshipping Him forever in their own languages. This scene is described twice in Revelation in chapter 5, verse 9 and also in Revelation 7:9, which states: “behold, a great multitude which no one could number, of all nations, tribes, peoples, and tongues (languages), standing before the throne and before the Lamb.”

Consequently, these principles related to the use of “heart” languages in missions do have a Biblical basis. It is a primary means by which God has ordained that the Good News should be proclaimed to and embraced by every language group in the world.

In addition to these Biblical concepts related to the use of “heart” language in missions, there are also some practical reasons for the use of these languages, even when the people who speak them also speak other often better-known and more widely spoken languages. Here are just a few thoughts that come from my own experience in missions and in ministering through various languages. This is neither exhaustive nor particularly academic, but rather based on my own (anecdotal) conclusions. However, I feel that there are probably several other experienced missionaries, who would share some of these conclusions.

Understanding

Quite simply, communicating with people through their heart language helps to ensure that they understand what it is that we are trying to communicate and that they understand it at a deep level. It is possible for them to understand technically the meaning of what we’re trying to communicate, if done through a “trade” language, at least on an intellectual level. However, if we really want them to understand and assimilate what we are trying to communicate that usually only really happens, when communicated through their “heart” language. In other words, the “heart” language makes the difference between someone getting the meaning of what we are trying to communicate as opposed to the significance personally in their own lives of what we’re communicating to them.

Identification

The use of the “heart” language aids in issues of identification on two levels. First, the “heart” language helps us to identify with the individual in a very personal way. It says to that person “I see you.” We identify with him/her in a deeply personal way, when we speak in the “heart” language. Second, the “heart” language helps us to identify Jesus with the individual as well as the entire language group. All of a sudden, the Gospel is not just for those “other people” generally referring to speakers of the majority, colonial or “trade” language, but it is also “for us.” In other words, “Jesus speaks our language just like one of us.”

Liberation

With identification of this kind, the “heart” language also brings a kind of liberation. In most cases, the “trade” language in question is something that was imposed upon these peoples without their consent or request. It was something forced upon them, and as such using them is often seen by speakers of these “heart” languages as a necessary evil and a constant reminder of their subjugation linguistically, culturally and often politically and nationally as well. Consequently, when we speak with them only through the “trade” language, rather than their “heart” language, we perpetuate some of these feelings, often opening wounds. But there is something really liberating for them, when we speak in their “heart” language, due to the strong sense of identification both at a personal level and with Christ.

Service

Here is an illustration that I have often used before. Forgive, therefore, the repetition. Suppose that two people with two different “heart” languages meet and want to communicate with each other. If conversation is to happen they need to have a communicative medium, which is usually the second language of one of the two people. In any such exchange and regardless of how proficient one might be, the person who is speaking his or her second language is in an inferior position in the conversation in terms of fluidity and ability to express opinions and desires. If we, the missionaries, wish to model the similar kind of humility and servanthood that Jesus demonstrated to His disciples as He washed their feet, it is incumbent upon us to serve the other person in this exchange by using OUR second language, allowing the other the freedom and superior position in the conversation.

Again, this is not exhaustive and it is based on my own experience over many years in multilingual missions ministry. However, if you want a much better researched (and written) explanation as to why missionaries use the “heart” language of the people they are trying to reach with the Gospel, you might want to read this article, Like Bright Sunlight: The Benefit in Communicating in Heart Language by Rick Brown.

Hopefully, by this point, I have addressed the first two issues that I mentioned in the beginning: (1) the nature of a “heart” language and (2) the need to use the “heart” language in missions. Now, I come to the final point, which is why we, at Linguæ Christi, feel such great need in pushing this point, i.e., the use of the “heart” language exclusively, repeatedly and incessantly, when it comes to the indigenous minority language groups in the European context. This is because of the frequent disconnect between our missions setting in Europe and that in other parts of the world, which are more familiar in the history of global missions. For example, if we take the previous scenario of the English-speaking Canadian missionaries going to serve in Ivory Coast, someone who would agree wholeheartedly that those missionaries would be expected to learn both French and Boualé and should do so in order to be effective communicators of the Good News to those people groups there might also say to us, when we say that we want to communicate the Gospel to Welsh speakers through Welsh, “Why? They all speak English.” There is a real disconnect here. Missiologically, it is the same principle that we use for learning Welsh to reach Welsh speakers, as one would use for learning Chinese if ministering in Chinese speakers or Boualé, if ministering among that language group, even though they might have proficiency in English or French or another “trade” language. The example seems to us very clear in the African situation, because the colonisers came from another Continent (Europe) and imposed their will (along with their language, culture, and even religion) on their new “subjects.” Consequently, we have no problem in using a “trade” language when needed but putting a real and greater emphasis on the “heart” language in the African context. What we forget is the fact that Europeans have been colonising their neighbours for centuries. The fact that so many stateless “nations” exist in Europe today is a testament to this reality. The goal of Linguæ Christi is to move beyond the “trade” (and yes, even “colonial”) languages of English, French, Spanish, Russian, etc. and go to the “heart” languages of Welsh speakers, Alsatian speakers, Basque speakers, and Komi speakers, etc. in order to win those language groups, the vast majority of which having been overlooked in terms of significant missions engagement, simply because it has often been easier to use a “trade” language, than the “heart” languages and justify our lack of good missiological practice with a similar quip, “but they all speak………”

I hope that this has been a helpful look at what is a foundational principle for us in our ministry in Europe. I look forward to explore with you other concepts with a connection to “language” over the next few months. Bye for now!